We can't import cheap homes; but we could import cheap EV cars

- 05.24.24

- Economy & Policy

- Commentary

Chief Economist Eugenio J. Alemán discusses current economic conditions.

We are free trade enthusiasts, in economic terms, even at a time when free trade has been losing some of its aura within the U.S. political system. Why? Because the existence of trade allows countries, in general, to achieve higher consumption levels than what they otherwise could achieve with what is called ‘autarky,’ which is a scenario in which a country doesn’t import or export from/to the rest of the world. This is not a fantasy or a fallacy, it is indisputable. Thus, we take the view ‘free trade is better than no trade’ and everyone wins with ‘free’ or ‘freer’ trade.

Having said this, there are instances where trade protection ‘may’ make sense, such as national security and, sometimes, temporary protection measures. Nevertheless, we always remain reluctant to make a case for some of the protection measures we see over the years. Our reluctance to accept protecting some industries with trade barriers is because often it means protecting industries that have become uncompetitive and inefficient and, typically, protecting them provides little incentives for these industries to make changes and attempt to become competitive again.

It is true that it is very difficult to keep domestic companies competitive if we consider domestic wages compared to wages in less developed countries. Sometimes there is an argument that some countries may be ‘dumping,’ which means that they may be selling some goods to foreign markets at a price that is lower than their production costs. However, sometimes the lack of competitiveness has to do more with failure to adapt and become more efficient than with anything else even though companies/industry lobby groups try to sell protection on anti-dumping arguments even if the evidence is lacking.

The auto industry is one of those industries that has failed to remain competitive in the past. Back in the 1970s and 1980s, the U.S. auto industry was caught off-guard by the increase in oil and gasoline prices, producing large, gas-gauging cars and trucks – sound familiar? At the same time, Japanese automakers were producing smaller, more efficient, and cheaper cars and started to flood the U.S. with cheaper cars that helped Americans deal with higher gasoline prices.

After complaints by U.S. auto manufacturers, Japanese auto producers started to use Voluntary Export Restraints (VER), to limit their automobile exports to the U.S. market. In 1982, and to bypass these limits, they started assembling automobiles in the U.S. Still, many tariffs and non-tariff barriers have continued to protect some segments of the U.S automobile market over time. Today, the imposition of tariffs on EVs from China is not only to protect U.S. auto manufacturers, but also Japanese, Korean, and German, etc., auto manufacturers that assemble automobiles in the US.

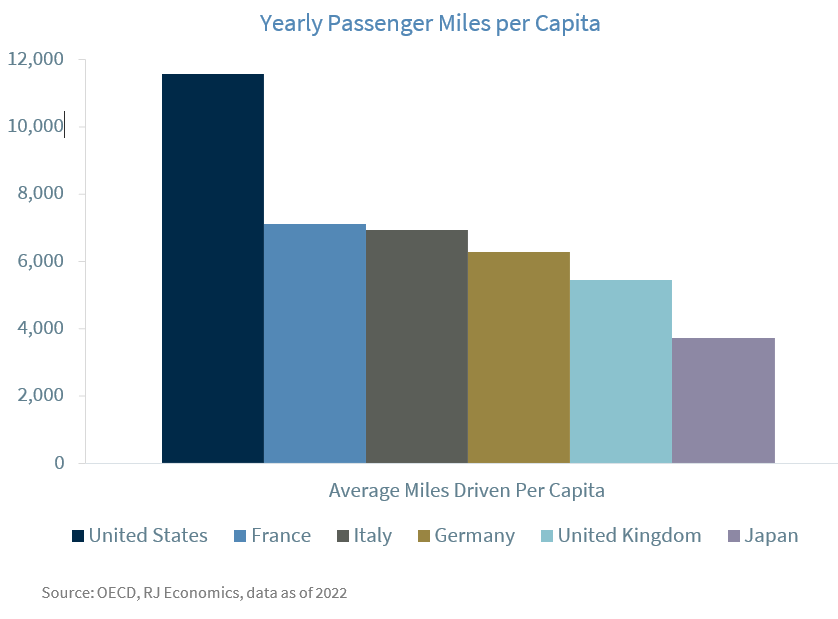

You may ask, what is the issue here? The issue is that automobiles are an essential working tool for American workers compared to what happens in other countries. Public transportation in the rest of the world helps workers commute every day so automobile ownership is, typically, used more for leisure and vacations than a necessary tool for work as is the case in the U.S., where public transportation is, for all intents and purposes, basically non-existent.

But there is an even more worrisome issue. Many U.S. auto manufacturers are no longer building cars for the mass market. They have continued to specialize in high-end models rather than cars for the masses, which makes accessing these expensive cars even more difficult for the average consumer. We recall a meeting several decades ago in which the chief economist of a large U.S. auto manufacturer argued that they were no longer targeting the production of cars for the masses but rather the production of specialized cars. They viewed their future car offerings as one car for the weekends, one for working, one for speed, one for retirement, one for grocery shopping, one for the grandkids, one for long trips, another for short trips, etc. That is, they seemed to have been targeting their efforts to producing different cars for different facets of an individual’s life, like sneakers, where people no longer had just one pair of sneakers for all sporting activities but one sneaker for each individual ‘sporting’ activity, i.e., basketball, running, walking, jumping, sitting, standing, playing tennis, stretching, etc., or something similar.

As a confirmation of such strategy, one U.S. auto manufacturer has already abandoned the production of sedans and is only producing high-end SUVs and trucks because those are the only profitable segments of the automobile market for them in the U.S. Furthermore, even the most important EV producer in the U.S. has scrapped plans to build an EV for the masses because it cannot compete with cheap foreign EVs.

Thus, if U.S. auto manufacturers are not going to compete in EVs for the mass market, why don’t we allow cheap foreign EVs to serve the mass automobile market while limiting, if we prefer, the importation of high-end EVs so we can temporarily protect the high-end EV industry in the U.S.?

This is nothing new or even innovative and we are not thrilled for even suggesting it because, as we said earlier, we are ‘free trade enthusiasts.’ However, the U.S. does it in the meat industry to protect and support the incomes of cattle farmers across the country, where we typically use quotas to complement U.S. meat production during periods of high demand and allow ‘lower’ quality meat to come in during some periods of the year. We also remember Asian countries’ strategies to protect their ‘high-end’ rice market, supporting the incomes of domestic rice producers while importing similar high-quality rice from other countries but then putting the imported rice in silos until it got close to a pre-rotted state and became ‘low-quality rice.’ After that, the low-quality rice was allowed to be sold to the masses at a lower price, which helped the less well-off in those countries.

Of course, we are not advocating that the U.S. follow the rice import strategy of Asian countries – buying high-end EVs, allowing them to deteriorate, and then selling them to the less well-off – but we could open only the low-end, cheap EV market to foreign companies EV imports, and thus allow the masses to reduce the cost of gasoline and the cost of buying ‘high-end’ EV luxury cars supplied by U.S. and foreign producers with plants in the U.S. This will help the less well-off and help reduce some of the inflationary pressures created by higher oil prices and higher luxury car prices.

The largest expenditure for any U.S. household budget includes the purchase of a home and the purchase of a car. We cannot import cheaper homes from overseas (homes are non-tradable goods) but we can make it easier, and cheaper, for American households to own a cheap EV.

Economic and market conditions are subject to change.

Opinions are those of Investment Strategy and not necessarily those of Raymond James and are subject to change without notice. The information has been obtained from sources considered to be reliable, but we do not guarantee that the foregoing material is accurate or complete. There is no assurance any of the trends mentioned will continue or forecasts will occur. Last performance may not be indicative of future results.

Consumer Price Index is a measure of inflation compiled by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Currencies investing is generally considered speculative because of the significant potential for investment loss. Their markets are likely to be volatile and there may be sharp price fluctuations even during periods when prices overall are rising.

Consumer Sentiment is a consumer confidence index published monthly by the University of Michigan. The index is normalized to have a value of 100 in the first quarter of 1966. Each month at least 500 telephone interviews are conducted of a contiguous United States sample.

Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (PCE): The PCE is a measure of the prices that people living in the United States, or those buying on their behalf, pay for goods and services. The change in the PCE price index is known for capturing inflation (or deflation) across a wide range of consumer expenses and reflecting changes in consumer behavior.

The Consumer Confidence Index (CCI) is a survey, administered by The Conference Board, that measures how optimistic or pessimistic consumers are regarding their expected financial situation. A value above 100 signals a boost in the consumers’ confidence towards the future economic situation, as a consequence of which they are less prone to save, and more inclined to consume. The opposite applies to values under 100.

Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards Inc. owns the certification marks CFP®, CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER™, CFP® (with plaque design) and CFP® (with flame design) in the U.S., which it awards to individuals who successfully complete CFP Board's initial and ongoing certification requirements.

Links are being provided for information purposes only. Raymond James is not affiliated with and does not endorse, authorize or sponsor any of the listed websites or their respective sponsors. Raymond James is not responsible for the content of any website or the collection or use of information regarding any website's users and/or members.

GDP Price Index: A measure of inflation in the prices of goods and services produced in the United States. The gross domestic product price index includes the prices of U.S. goods and services exported to other countries. The prices that Americans pay for imports aren't part of this index.

The Conference Board Leading Economic Index: Intended to forecast future economic activity, it is calculated from the values of ten key variables.

The Conference Board Coincident Economic Index: An index published by the Conference Board that provides a broad-based measurement of current economic conditions.

The Conference Board lagging Economic Index: an index published monthly by the Conference Board, used to confirm and assess the direction of the economy's movements over recent months.

The U.S. Dollar Index is an index of the value of the United States dollar relative to a basket of foreign currencies, often referred to as a basket of U.S. trade partners' currencies. The Index goes up when the U.S. dollar gains "strength" when compared to other currencies.

The FHFA House Price Index (FHFA HPI®) is a comprehensive collection of public, freely available house price indexes that measure changes in single-family home values based on data from all 50 states and over 400 American cities that extend back to the mid-1970s.

Import Price Index: The import price index measure price changes in goods or services purchased from abroad by U.S. residents (imports) and sold to foreign buyers (exports). The indexes are updated once a month by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) International Price Program (IPP).

ISM New Orders Index: ISM New Order Index shows the number of new orders from customers of manufacturing firms reported by survey respondents compared to the previous month. ISM Employment Index: The ISM Manufacturing Employment Index is a component of the Manufacturing Purchasing Managers Index and reflects employment changes from industrial companies.

ISM Inventories Index: The ISM manufacturing index is a composite index that gives equal weighting to new orders, production, employment, supplier deliveries, and inventories.

ISM Production Index: The ISM manufacturing index or PMI measures the change in production levels across the U.S. economy from month to month.

ISM Services PMI Index: The Institute of Supply Management (ISM) Non-Manufacturing Purchasing Managers' Index (PMI) (also known as the ISM Services PMI) report on Business, a composite index is calculated as an indicator of the overall economic condition for the non-manufacturing sector.

Consumer Price Index (CPI) A consumer price index is a price index, the price of a weighted average market basket of consumer goods and services purchased by households. Changes in measured CPI track changes in prices over time.

Producer Price Index: A producer price index (PPI) is a price index that measures the average changes in prices received by domestic producers for their output.

Industrial production: Industrial production is a measure of output of the industrial sector of the economy. The industrial sector includes manufacturing, mining, and utilities. Although these sectors contribute only a small portion of gross domestic product, they are highly sensitive to interest rates and consumer demand.

The NAHB/Wells Fargo Housing Opportunity Index (HOI) for a given area is defined as the share of homes sold in that area that would have been affordable to a family earning the local median income, based on standard mortgage underwriting criteria.

The S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price NSA Index measures the change in the value of the U.S. residential housing market by tracking the purchase prices of single-family homes.

The S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller 20-City Composite Home Price NSA Index seeks to measures the value of residential real estate in 20 major U.S. metropolitan.

Source: FactSet, data as of 7/7/2023