Economic Concept: Supply and Demand

How to know when Enough is Enough

I love to shop and buy new things. And, of course, who doesn’t want the very best? The problem is that most people only have so much money; so how does someone decide what will most satisfy his or her desires and needs, given the limited resources he or she has? The answer: through prices determined through the economic concept of “Supply and Demand.” It helps you to know when enough is enough.

Remember, economics is the study of the production, distribution and consumption of scare resources (scarcity: a condition of limited resources and unlimited wants). In light of scarcity, we are forced to decide what we want most, given the resources we do have, and make choices. We must determine our unique preferences, make trade-offs and sacrifice one thing for another. In other words, scarcity requires us to economize. If we economize effectively, we maximize our satisfaction, given our limited resources. This is the heart of economics.

Fortunately, two simple economic concepts illustrate how free markets determine the best use of these scarce resources, namely, “supply” and “demand.”

- Supply is how much of a good or service producers will offer at any given price.

- Demand is how much of a good or service consumers desire at any given price.

I wish I had a dime for every time I have heard. “It’s just supply and demand!” when someone is asked to explain a market. In fact, these two terms are more powerful, intricate and important than most people realize. Remember, because prices (relative to other things) determine how scarce resources are allocated (to alternative uses), it is important to understand what affects prices (after all, standards of living depend on how effectively we use what we have). The more accurately an economy expresses the unique preferences of all individuals, the more people can be satisfied

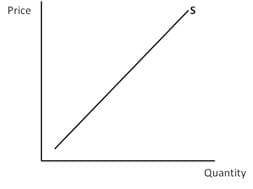

Supply

The amount of any good or service produced rises with the price of that good or service (as price rises, the quantity supplied rises). Here is what that relationship looks like:

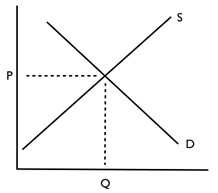

Demand

The amount of any good or service demanded falls as prices go up (as price rises, the quantity demanded drops). Here is what that relationship looks like:

Now before you ask, yes, everyone does have their individual preferences about what they want and how much they are willing to pay for it. Some people are willing to pay $60,000 for a Cadillac; others would rather buy a Toyota for $30,000. Likewise, every business is not able to produce (or supply) the same quantity of goods at the same price as others. Some businesses are inefficient or want a higher profit, so they will only offer a certain quantity of their goods/services at a price higher than other businesses. Still, the total demand and supply curves for any given product or service, represents the combination of all individual choices (preferences) in the society. The interaction of supply and demand (representing all individual choices) determines free market prices (and the optimal allocation/uses of scarce resources). At this equilibrium (balance), maximum desires are satisfied given the limited resources available.

Of course, competition is a requirement for this to work. Producers cannot force prices on consumers and vice versa. There needs to be a free interaction between suppliers and consumers to arrive at a free market price. In a competitive market, a producer cannot set their price higher than everyone else; otherwise, consumers will not buy their product (they will buy the product from the less expensive producer). Likewise, consumer cannot demand a “below market” price; otherwise, producers will simply sell to the consumers who are willing to pay more.

Now you may think, “This is a messy process that could produce random results,” or “We would be better off if someone really smart just set prices, so individuals don’t have to keep making all these adjustments.” Again, in the words of John Pinette (God rest his sole), I say, “Nay, Nay!”

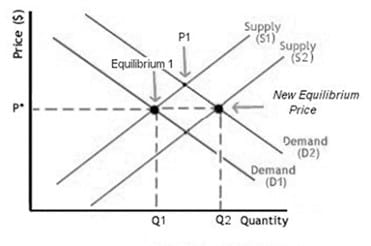

Indeed, it’s an insurmountable task for even the smartest experts to determine efficient prices in a dynamic economy. However, individuals, facing the relatively few exchanges they deal with every day, can be quite accurate about their preferences and alternative uses of their scarce resources. Supply can shift over time (as a result of new technology, etc.: S1 to S2). Demand can shift (as a result of new preferences, etc.: D1 to D2). No matter, prices adjust to reflect these new conditions. Here is what that process looks like:

What happens if a price is forced onto an economy through government control? Well, unless that “centrally-planned” price is exactly the same as the price that the free market would have determined, then a surplus or shortage will result (both of which conditions result in a waste of resources).