Economic Concept: Marginality – When Enough Is Enough!

Have you ever looked forward to having some great food and drink? Maybe it’s a family holiday or going to your favorite restaurant. After you indulge yourself, at some point you are feeling, “Oh Man! I could not eat another bite or drink another glass!” At the start, you place a much higher value (want) on the scrumptious food and fine libations than you do after you have had your fill… Right?!

Even though the world we live in is characterized by scarcity (not simply that there may be shortages of some goods and services from time to time; but the fact that there is a limit to total resources, but no limit to total human wants), with respect to individual consumers, and individual goods and service—sometimes “enough is enough.” This is important to an understanding of what is behind the demand (and supply) curve for goods and services.

As I have pointed out before, economics deals with the allocation of scarce resources (which have alternative uses). In a free market, these scarce resources are allocated to their most valuable uses when prices reflect the unique preferences of individual producers and consumers. The quantity of any product or service supplied (or demanded) by producers and consumers, is affected by price (higher prices induce producers to make more and consumers to want less, and lower prices induce producers to make less and consumers to want more). This dynamic process provides the incentive for prices to move toward the level where supply meets demand (at which point the allocation of scarce resources has created the maximum amount of satisfaction for society).

It is hard to measure the actual preferences of individuals, since preferences deal with the perceptions of how much something is worth. I prefer tacos to burritos. You might prefer pizza to tacos. I would pay more for a taco than a burrito and you would pay more for a slice of pizza than a taco. What we DO know is that these preferences are revealed through free-market prices, when there exists true competition for goods and services.

What is Marginality?

“Marginality” is a concept that describes one thing being affected when another thing changes slightly. The adjective “marginal” is typically added to an economic term to describe what happens when there’s a slight change in another factor. For example, “marginal cost” would describe the change in total cost, when one more or one less unit of a product or service is produced. In other words, if I produce less, how much less does it cost me? If I produce more, how much more does it cost me? This change in cost is the “marginal cost.”

What is Utility?

In economics, “utility” is a concept used to describe how much a consumer values a product. Utility is the capacity of a good or service to satisfy wants, as perceived by each consumer. Utility cannot be directly measured (since each person has different desires and perspectives on what they consider valuable). It can only be observed through the revelation of preferences (as expressed through market prices). However, we can deduce a couple of things about utility in real life:

- We derive increased utility from consuming more units of a good or service, up to a point (at which we are satiated).

- We derive a smaller increase in utility from each additional unit consumed, as the amount we consume increases (decreasing marginal utility).

Think of it this way: after exercising, I really value that first glass of cold water (and I might pay several dollars for it, if I didn’t already have water). However, after a few glasses, I doubt I would pay much for another. After a few quarts, I would probably rather puke than drink more. Although consumers may derive additional total satisfaction from an increase of a good or service, they do not get as much marginal benefit from each additional unit consumed.

Marginal Utility and the Consumer

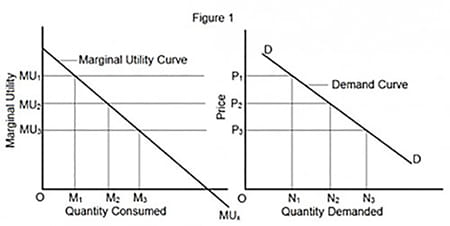

On an individual basis, consumers will continue to buy a good or service until the marginal utility (as their preferences perceive it to be) of the last purchase equals the market price for that item. At such a point, the next incremental purchase would have a marginal utility less than the market price, so why would the consumer buy more. It’s like eating a fabulous dessert for the first time. The experience was SO GOOD, you say you LOVE it and can’t wait to have it again, so you order another. The second one may not be so exhilarating, because the WOW factor is gone and your tummy is getting full. Therefore, since the second experience was not as powerful, ordering a third may not be so appealing and leave you wondering if the price is worth it. Enough is enough at the market prices.

This is where the demand curve (that I described in previous blogs) comes from. As prices fall, the quantity demanded by all consumers increases (because there exists a greater quantity at which marginal utility is higher than the now lower prices). In other words, if my utility of buying one or one more is less than the market price, I will not make the purchase; but at a lower price, well, now my marginal utility may exceed the cheaper price, so I will make the purchase. Likewise, if the market price rises, there are fewer consumers who see the value (the price exceeds their marginal utility).

Marginal Cost for Producers

A similar “marginal concept” exists for producers. Producers need to cover the costs of materials, capital, labor and a profit for their efforts and risks. Unlike “utility,” total cost is more easily quantifiable by simply accounting for what has to be paid for each underlying cost. However it is the “marginal cost” of producing an additional unit of a good or service that determines whether a producer will increase the quantity they supply given the market price.

For producers, the cost of production determines how much they will produce at any given price. So long as the market price is equal to or greater than the marginal cost of production, the producer will increase output. If it’s profitable to make more, more will be made. A producer will stop production whenever the market price is below the marginal cost. This is where the supply curve (that I described in previous blogs) comes from. When the profit shrinks with lower prices, fewer items are produced. As prices increase, the quantity supplied by producers increases (because a greater quantity can be supplied at which the marginal cost is below that higher market price). Likewise, if the market price falls, only a smaller quantity can be produced at which the marginal cost is at or below the now lower price.

Labor: Where the Consumer becomes the Producer

Again, the labor market can be described in a similar construct as other goods and services. I have pointed out that the labor market uses special terms and is plagued by emotional arguments. However, labor is simply priced in terms of wages. Workers are the suppliers of labor and employers are the consumers of labor. Once you get this, the labor market functions the same way as other markets for good and services.

In the case of labor markets, what is hard to quantify is the marginal cost (to workers) of providing labor. Much like “utility,” the cost of labor (to each worker) depends on each workers preference (in terms of exchanging their leisure time for working). Since there are limited hours in the day, days in the week, weeks in the year and years in a life, then the cost of working is the leisure time lost. Workers who place a higher value on leisure time will project a higher cost of their labor. Workers who value leisure less, will project a lower cost of labor. For each worker, the marginal cost of their labor depends on their personal preferences for leisure.

As with “utility,” this cannot be directly quantified, but is rather expressed in the wages (price of labor) that each worker requires in order to give up some leisure. Any given worker will not work beyond the point where the marginal value of their leisure (their marginal cost of their labor) is greater than the wage rate. This is the source of the supply curve for labor that I described in previous blogs. As wages increase, the quantity of labor supplied by workers increases (because a greater quantity can be supplied at which the marginal cost of labor—leisure—is below the wage rate). Likewise, if the wage rate decreases, a lower quantity of labor can be supplied where the marginal cost is at or below the lower wage.

If you think of it this way, “Why would I work at company “A” who pays $10 an hour, which would require me to work 60 hours a week to meet my needs, when I can work for company “B” who pays $15 an hour, and I can work less to meet my needs and have time off to enjoy it? Someone who needs the money badly, therefore leisure is not a priority, would work for company “A” for $10 an hour.

Marginal Productivity

As for the consumers of labor (employers), their marginality can be more easily quantified. The marginal productivity of labor is simply the additional value added to production for each additional unit of labor. Marginal output, revenue, net profits, etc. are measurable items. Therefore, an employer can readily calculate the marginal productivity of labor. Employers will demand additional labor up to the point where the marginal productivity of labor meets the wage rate (the market price of labor). Employers will not demand additional labor (employ more workers or demand more hours of work) when the wage rate exceeds the marginal productivity of labor. This is the source of demand curve for labor that I described in previous blogs. As wages fall, the quantity of labor demanded by employers increases (because there is a greater quantity of work at which marginal productivity is higher than the lower wages—they can produce more for less). Likewise, if market wages rise, there is then a lower quantity of work at which the marginal productivity of labor is at or above that higher wage.

Marginality is important to understanding the incentives for producers and consumers of goods, services and labor, to adjust supply and demand toward a free-market price (at which supply and demand are in equilibrium, and the allocation of scarce resources has maximized standards of living). Can you see how impossible it would be for central planners to arrive at the right price and quantity to reach such an efficient allocation of resources? Only individual consumers, producers and workers can decide what is best, according to their individual preferences. Economics helps us understand the process, but only the free market can reveal the prices and quantities at which scarce resources produce maximum welfare for society.